Read the full paper here

Read the full paper here

WPATH is the World Profesional Association for Transgender Health. The organisation recently released new standards of care which our Ministry of Health has said it will rely on. They said

Our approach to the provision of gender affirming health care will continue to be guided by health professionals and Rainbow communities, including the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care Version 8 (SOC8).

These updated guidelines will provide updated assessment, support, and therapeutic approaches for transgender and non-binary people

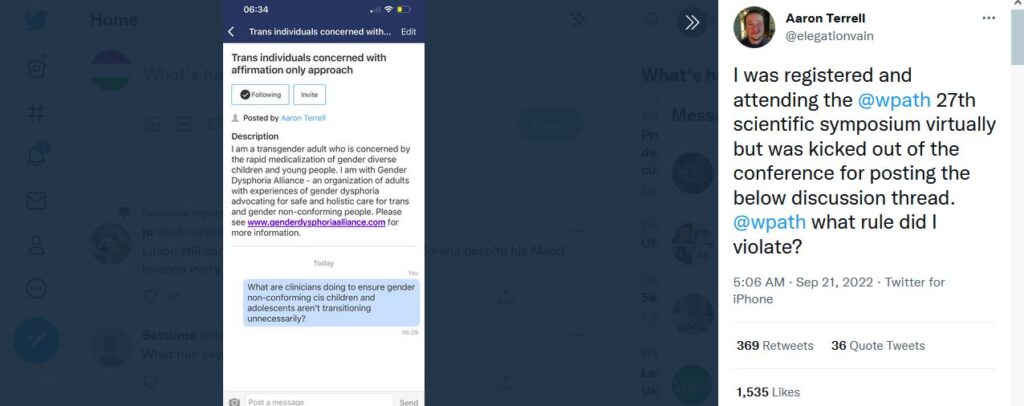

So they seem to have really nailed their colours to the mast. But WPATH’s Standards of Care (SOC 7) published in 2012 fared poorly in reviews of its quality. WPATH’s renewal project for SOC 8 took 3 1/2 years. Its launch was delayed and chaotic. In the days immediately after its publication a correction was published removing all but one of the age limits for medical and surgical treatments. (UPDATE: Court documents released in 2024 have revealed that this was due to political pressure) The US edition of the Economist magazine called it ‘a mess’. A researcher, Pablo Expósito-Campos, said on Twitter that his work had been misrepresented. A conference attendee was summarily thrown out of the WPATH conference for posing a question.

The New York Times’ Emily Bazelon wrote the first article pointing out that there were different views about gender medicine.

I did a deep dive into the new standard to see whether it warrants the NZ Ministry of Health’s confidence and whether it provides – as it claims – evidence-based healthcare.

Read the full paper here

To do this I looked at the criteria that WPATH said it was using to create the Guideline to see whether it measured up. WPATH reports that it was guided by World Health Organisation and the US National Academies of Medicine advice for creating guidelines. The National Academies of Medicine use 8 criteria for creating and assessing Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPG).

I discovered that the literature review did not find (or use) any of the systematic evidence-based national and sub-national reviews of child and adolescent gender medicine that had taken place. (UPDATE: These were the predecessors to the CASS review.)

The fate of the systematic reviews undertaken to support the Guideline is not clear and neither are arrangements for dealing with conflicts of interest.(UPDATE: Court papers released in 2024 have shown that Johns Hopkins University was pressured not to publish these papers.)

However the real elephant in the room is that of WPATH’s stance on gender medicine. Informed partly by the early sexologists like Harry Benjamin and partly by a post-modern framing the main idea they have is that everyone has a gender identity that either matches (or does not match) their biological sex. This is a belief that has no basis in biology or medicine. Moreover WPATH treats these two options as equivalent.

But how can a lifelong and heavy burden of medication and surgery to match your body with your perception of it be equivalent to learning to accept to live in and love your own body? Here is a brief overview of the criteria that WPATH say they used and some of the problems with the resulting standard.

| US National Academy of Medicine Clinical Pratice Guideline | WPATH SOC 8 performance against the Clinical Practice Guideline | |

| 1 | Transparency | There is much that is unclear about the Guideline. Why were the age limits for medication and surgery removed after the Guideline was published? Why was the ethics chapter removed? Why were people with disorders of sexual development included as ‘intersex’ when no intersex organisations are recorded as having been consulted and the two groups are almost completely different? Why is it not made clear that the SOC is based in a belief in gender identities which are unproven. |

| 2 | Conflicts of interest | Conflicts of Interest were notified but there is no information about how they are managed. A review of SOC 7 found considerable cause for concern. |

| 3 | A systematic review | Which systematic reviews were completed? Where were they published? The SOC does not reveal this information. (UPDATE: We now know they were suppressed by WPATH) |

| 4 | Guideline Development Team Creation | The chapter authors and team members are listed. There is strong preference in favour of medical and surgical intervention. Practitioners who are sceptical were not included.(UPDATE: The Cass review assessed WPATH SOC 8 as a weak guideline dependent on recycled references) |

| 5 | Establishing evidence foundations for guideline recommendations | The literature cited does not include the international evidence-based reviews that show that gender medicine for children has an evidence base that is ‘very low’. |

| 6 | Rating the strength of, and articulation of recommendations | Many recommendations go way beyond clinical guidance seeking to influence in government and education. The Guideline recommendations lack codified information about 1. the strength of recommendation or certainty of evidence attached to them. 2. justification about the balance of desirable and undesirable consequences for each of the recommendations. 3. evidence synthesis attached to each of the recommendations. 4. values and preferences, which shape the recommendations Many Recommendations are duplicated and some are unsupported by any evidence in favour of their use. |

| 7 | External (independent) review | There is no evidence provided that a review has happened. |

| 8 | Updating plan | There is no evidence of a plan. |

| Overall | Drafting issues, duplication, unreadable sentences, referencing mistakes and omissions, no signposting about how to use the document. |

Read the full paper here

Latest Comments