In 1988 as part of the report of the Royal Commission on Social Policy Values Party member Catherine Benland wrote about the S-Factor. Why she wondered would happen if our spiritual values, which I take to understand as our deepest values and best selves were to be part of the consideration in the development of public policy.

She did not mean that the church should influence the state. Her context was broader than that. She considered the human potential movement to be part of the expression of human spirituality for example.

She wrote

Have not millions expressed their quest for personal fulfilment primarily through tribal, world, or personal religions—or the modern substitutes for these in the human potential movement? Real spirituality is not icing on the cake, it is not a once-a-week exercise: it permeates every second, every place, every relationship. Social services cannot exist in isolation from it; providing houses, hostels, hospitals, hospices will not contribute to the personal fulfilment of their occupants unless the S-factor is taken into account by architects and administrators.

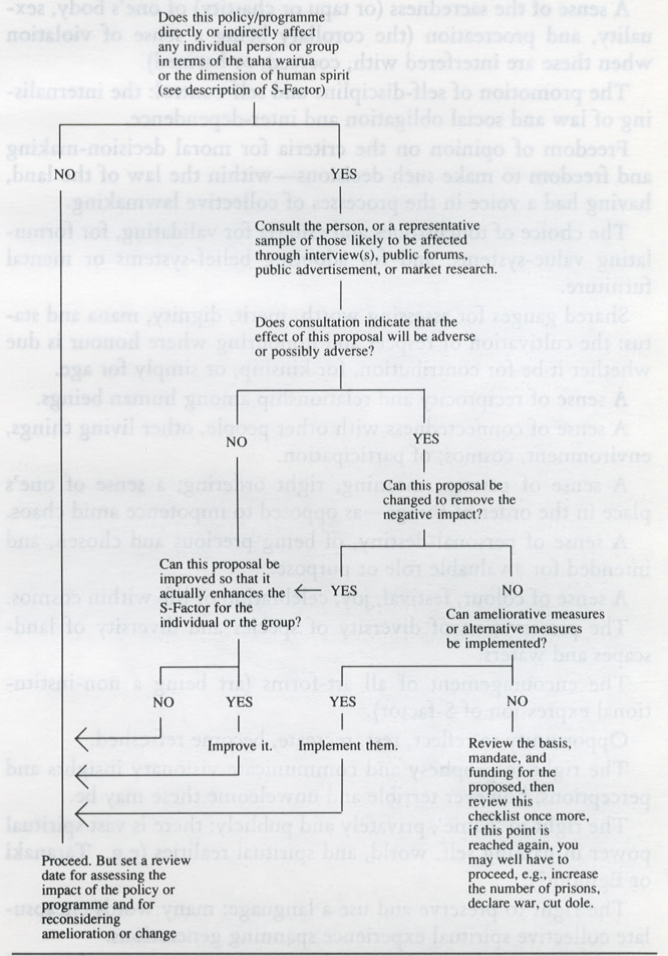

Benland’s article is attached as a pdf and she also created a policy workflow considering the S-Factor.

The issue it raises for me are uncomfortable. We regularly allow that Māori spiritual context has a place in public policy – and this has been the case at least since the Royal Commission’s report. But not Pākehā spirituality. Even to allude to it is somewhat embarrassing. However this was not always the case. In the 1930’s in NZ and in the 1940’s in the UK commentators regularly spoke of the respective Labour government’s welfare policies of those times as “applied Christianity”. What do you think is going on here?

Catherine made a number of suggestions about what, honouring this spirit would entail in terms of public policy. Here are the suggestions.

- The Royal Commission should make a place for acknowledging the S-factor and for recommending that impacts of social policies and programmes in terms of the S-factor be considered from the outset of planning, monitored throughout implementation, and reviewed after completion.

- Freedom of conscience, belief, religious adherence and practice, and worship.

- Preservation of sacred places, buildings, objects, customs, and literature.

- Access to wellsprings of empowerment and affirmation, e.g., wilderness, distant horizons. Access to people with mana, spiritual experience, and spiritual skills.

- Access to spiritual communities and meeting places, and freedom of assembly; the right to live in an open or closed religious community, e.g., a monastery.

- Opportunity to provide and for children to receive education influenced by the S-factor especially the :

- -criteria for morality;

- -motivation for altruism

- -empowerment for fulfillment of potential

- -grounds for personal and collective hope

- Access to pastoral care and the opportunity to minister spiritually to others and to transmit received and inspired wisdom.

- Freedom to respond to the sense of duty and to fulfil moral, spiritual, religious, and relational obligations.

- A feeling of having roots, turangawaewae, belonging to motherland or fatherland, feeling bonded to, and nurtured by Aotearoa/New Zealand, whether non-Maori or Maori, whether iwi or tauiwi, tangata tuatahi or tangata tuarua.

- Access to at least a subsistence level of economic and physical wellbeing, which is a precondition for spiritual wellbeing

- A minimal level of freedom from household violence; street violence; civil, international, or global war and the prospect of continuing peace, justice, and freedom.

- A sense of the sacredness (or tapu or chastity) of one’s body, sexuality, and procreation (the corollary being a sense of violation when these are interfered with, coerced, or harmed).

- The promotion of self-discipline and self-control: the internalising of law and social obligation and inter-dependence.

- Freedom of opinion on the criteria for moral decision-making and freedom to make such decisions—within the law of the land, having had a voice in the processes of collective law-making.

- The choice of touchstones and criteria for validating, for formulating value-systems, and for adopting belief-systems or mental furniture. Shared gauges for assessing worth, merit, dignity, mana and status:

- the cultivation of respect and honouring where honour is due whether it be for contribution, for kinship, or simply for age.

- A sense of reciprocity and relationship among human beings.

- A sense of connectedness with other people, other living things, environment, cosmos; of participation.

- A sense of pattern, meaning, right ordering; a sense of one’s place in the order of things—as opposed to impotence amid chaos.

- A sense of personal destiny, of being precious and chosen, and intended for a valuable role or purpose.

- A sense of colour, festival, joy, celebration of life within cosmos.

- The preservation of diversity of species and diversity of landscapes and waters.

- The encouragement of all art-forms (art being a non-institutional expression of S-factor).

- Opportunity to reflect, rest, recreate, become refreshed.

- The right to prophesy and communicate visionary insights and perceptions, however terrible and unwelcome these may be.

- The right to ‘name’, privately and publicly: there is vast spiritual power in naming self, world, and spiritual realities (e.g., Taranaki or Egmont?).

- The right to preserve and use a language: many words encapsulate collective spiritual experience spanning generations.

- Protection of the intellectual from persecution, censorship, and the crushing of curiosity.

- Protection for the sensitive from brutalising.

- Encouragement, not clobbering, for ‘tall tulips’, for those with talent and vision, for entrepreneurs, for initiative and creativity.

- Protection from being spiritually diminished and coerced by structures, processes, and institutions, e.g., being identified by number not name.

- Jobs, housing, services, city planning and management, land use, etc., which does not diminish the S-factor.

- Opportunity in terms of land allocation and housing flexibility to live in an extended family (based on blood or choice or both, e.g., Centrepoint).

- Access to adult status (often denied to those who are never employed, never educated, or handicapped).

- The fostering of, and transmission of, skills of parenting, homemaking, peace-making, reconciling, mediating, facilitating, and building community.

- The countering of materialism and consumerism.

- An understanding of what causes inhumanity and what promotes humanitarianism.

- A tenderness and compassion for the weak, the foolish, the losers, the dependant, the handicapped, the deprived, the imprisoned, the refugees, the marginal, the oppressed, the victims, the maimed, the ill, the dying: a commitment to share, heal or support, encourage or empower.

- Especial consideration of the S-factor in questions of mental health care and institutions.

- Access to healing for psychic disorders and spiritual malaise, which can be manifested as mate Maori, musu, apathy, fatigue, addiction, violence, fanaticism, despair and suicide.

- The ability to achieve holistic health, autonomy, and psychic maturity and coping.

- The right to struggle against spiritual barriers or tangible barriers that impede the flowing and flowering of the spirit.

- Faith in virtue, honour, and trust; hope for self, family, community, iwi, society, world, other species, and the future; love for self, family, community, iwi, society, world, other species, and future generations as yet unborn.

- A sense of contact with Source, God, Matrix, Ground of existential courage, Universal Spirit, or Multiple Deities.

Latest Comments