In March 2016 the Labour Party held its Future of Work Conference. Notable speakers were Guy Standing, author of The Precariat and former Clinton-era Secretary of Labour Robert Reich. The idea of a Universal Basic Income (UBI) was raised in a discussion paper as being potentially the single most popular idea being discussed internationally to address both increasing inequality. Internationally there are several UBI pilots planned and thinktanks here and overseas have developed detailed costed models.

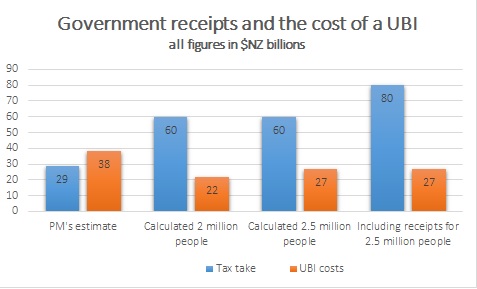

There was a flurry of coverage in social and mainstream media. Significantly, in a video and reportage that was widely circulated our Prime Minister, John Key, described Labour as ‘barking mad’ and cited figures that put the cost of a UBI – at $38bn – a figure greater than the $29bn per annum he said was the total tax take. Both the comment and the figures were repeated widely and without question. Labour politicians were soon on the defensive. Grant Robertson said that UBI might be a goer in 15 years. Later Labour leader Andrew Little was forced to concede that the flagship conference had in fact contributed to a “bad week for Labour”. A wider debate on the subject was cut short.

However the quoted figures were misleading. According to the IRD the 2014-15 tax take was almost $60bn. More than ½ is GST. Gareth Morgan has reported that when receipts for services from government – passport applications, driver licences, state house rents – government income is actually closer to $80bn per annum and his article made broadly the same point as this. Much of the public debate on this topic appears willfully misinformed. The Prime Minister’s figures on the costs of providing a Universal Basic Income were correct but misleading. The figures included more than a million people who already receive either superannuation, job seeker’s allowance or other welfare payments. A further 350,000 families receive supplementary Working for Families payments. Much of these costs (nearly $20 bn in 2015-16) would not be part of the additional costs of delivering a UBI. The effective cost of a UBI using the model discussed at the conference would be the NZ adult population of between 2m & 2.5m who are not already paid through social benefits.

2M people * $11000 = $22M 2.5M people * $11000 = $27m

Even if the cost of a UBI were greater than the entire tax gathered that in itself, is no reason for ruling out a discussion about a radical change to the welfare system. New Zealand’s taxation levels are already low by OECD standards. It is known that many of New Zealand’s wealthiest companies and individuals minimise tax very effectively using trusts, offshore profit centres and other methods.

As ordinary citizens, we should have the opportunity to look behind the words of the powerful, especially when it appears information and figures seem to have been presented to score a political point. This is not the first time denigrating language and misleading information have ensured that ideas new to New Zealand, but well accepted elsewhere in the world, are not able to be properly examined and debated. To take just the financial examples that have been raised but rubbished by government politicians and the media are: capital gains tax, a carbon tax, land tax, taxes levied on unhealthy food, the campaign for a living wage and quantitative easing for the people – each of which could play a part in progress towards a more equitable and sustainable economy. Politics is a contest of ideas requiring facts and information. The ‘truth’ is not a unitary concept. When, as in this case, an idea is denied oxygen by dint of misleading analysis and denigrating comments being taken at face value by the media we are all deprived of the opportunity to examine ideas on their merits.

There have been many positive aspects to a Universal Basic Income where it has been trialled. It provides a buffer for people between jobs and allows people to reskill. In Manitoba a trial in the 1970s not only reduced poverty but also the cost of hospital and mental health services. Other evidence mentions massively increased levels of entrepreneurship, which the often punitive benefit system does not, and because it is ubiquitous there are low costs of administration and low levels of fraudulent behaviour. A UBI would enable people to do much of the caring work in society that the government cannot – and the market will not – pay for. It would reduce the incidence of begging and homelessness. Finally, as technology cuts a new swathe through long-established skill-sets it would ensure we all have a stake in society.

In Owen Jones’ recent book The Establishment he wrote about the boundaries around public debate that benefit the powerful at the expense of ordinary people. He described that a willingness to maintain “a fiction about what is and isn’t politically possible” that undermines citizenship and democracy. Ensuring that citizens are presented with the facts and a range of opinions is a centrepiece of democracy. The responsibility for this is shared. Politicians themselves, academics, think-tanks and experts, a critical media and individual commentators all play their part in helping unpick the issues. Informed debate relies on accurate information, and when misleading information goes unquestioned, we are all denied the opportunity to test new ideas and New Zealand is the poorer for it.

Latest Comments