Children and the Environment: Nurturing a democratic imagination Bronwyn Hayward 2012

Are there better kinds of democracy and do we need to do something different to face the challenges ahead?

Jens Stoltenberg, Norwegian Prime Minister said – following the appalling shootings on Utøya Island in 2011 – “We will stand by our democracy. The answer [to violence] is more democracy, more openness, but not naivety.” It was a courageous and humanity- confirming response in the face of the gunman’s avowed intention of creating the conditions where Norway’s Muslims and other minorities would be forced out of the country.

Stoltenberg’s response was in contrast to a frequent and darker approach. When Naomi Klein wrote The Shock Doctrine she listed many situations where governments have used crises to introduce policies that intrude on democratic freedoms. In New Zealand the government’s ‘solution’ to a long-standing impasse at Canterbury Regional Council and the relative disempowerment of the Christchurch City Council in the aftermath of the earthquakes are local examples of how the response to crises are by no means always ‘more democracy’.

What more valuable work could there be then, than to educate and empower young people to use and value democratic approaches and that is what Bronwyn Hayward’s book is about. Bronwyn is a Canterbury-based academic and has written extensively on the environment and children’s issues. Her book, Children and the Environment: Nurturing a democratic imagination, was launched last year at a parliamentary event co-hosted by Green, Labour and National MPs. It speaks to the necessity of raising future generations who have trust in their role as actors on democratic issues.

The context: weakened democratic institutions

She makes the case that the best response to future environmental challenges is like Stoltenberg’s prescription – “more democracy”. Her context is the current geo-political situation of worldwide recession / depression, a growing gap between rich and poor, environmental and ecological degradation and a looming climate change and energy crisis. In particular she focuses in on the 30 + years of neo-liberal ascendancy in politics and Chicago-school economics in the West and its impacts – the decreasing robustness of democratic institutions and the withering of empowered citizenship in favour of people as consumers. To counter this she describes in detail the different kinds of social engagement and activism and the positives these provide to communities and society. Of course this is more difficult than it seems: “community organised advocacy and resistance are not always helpful,” she says, and, “a rabble is not a democracy – and community organisations can embed injustice and discrimination.” Democratic capabilities need to be grown with open eyes and with care.

The research

The research was carried out in Northland and in Christchurch before and during the earthquakes. She comments on the possible enduring effects of the lack of democracy in Christchurch on children as CERA has subsumed the role of the Council, first in the suburbs and subsequently in the city. In contrast she also writes about the higher levels of local citizen engagement engendered by the post-earthquake crisis as the city moves toward transitions and recovery.

The research involved 4 years of interviewing 250 children aged 8-12 from 10 schools covering a variety of school settings urban/ rural, high / low decile, large and small schools, ethnically diverse and broadly monocultural. Through interviews, classroom exercises and group discussions the research identified the different levels of engagement children had had with democratic experiences. These differences resulted in a typography to describe the children’s level of capability with democratic engagement. Some children were “streetwise sceptics” – they “knew stuff” but felt disempowered and unsupported in engaging democratically with their own communities. Other were “self-helpers” or “green entrepreneurs” who are engaged in a limited way, but “digital citizens” and “team and tribal players” were children who were more fully able to be effective about environmental issues in their own lives. Surprisingly, the extent to which the children understood their capacity for agency with respect to their own environments bore little relationship with school decile level and Maori children at a Kura Kaupapa had had greater exposure to discussions about decision making and consequently were amongst those who were able to act with greater assurance.

What is needed to be an effective actor?

Bronwyn then describes what makes useful engagement possible for children. They need an awareness of the different aspects of the environment and how they impact locally. They need to be exposed to attitudes that indicate that public action is possible and to have observed deliberation and decision-making by others. In the book, actual opportunities to engage with issues included things like the running local parks and playing fields. Finally, they need to be allowed to understand and articulate an issue, to develop options and preferences about desired future states, and to engage with the mechanics of bringing about those future states.

What would a deep democracy look like?

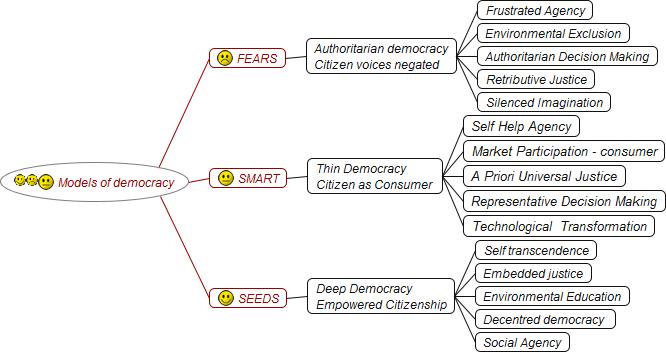

Fig: Modelling different types of democracy

If building a sense of community empowerment is the objective, then an important question is how this can be made visible in a teaching setting. Bronwyn devised three models to describe the possible types of engagement. The ‘SEEDS’ model of ecological citizenship education as an approach. The elements are:

- Social agency,

- Environmental Education,

- Embedded justice,

- Decentred democracy and

- Self-transcendence.

SEEDS is a deep democracy model which would allow the fundamental drivers of inequality, social justice and dangerous environmental change to be countered by citizens’ action. She contrasts this model with two others. The direct opposite is ‘FEARS’ (Frustrated Agency, Environmental Exclusion, Authoritarian Decision Making, Retributive Justice, Silenced Imagination ) – an authoritarian model where citizen agency is frustrated by command and control responses which limit the ability to imagine and effect change. In between lies ‘SMART’ (Self Help Agency, Market Participation, A Priori Universal Justice, Representative Decision Making, Technological Transformation) – which Bronwyn describes as “thin democracy”. This is the democracy of property rights, self-help, social media and citizen as consumer rather than public actor. It is the minimal, 1-vote-every-three-years system we all operate within in the NZ adult world, where the democratic voice can seem to lack power against money, power and market forces.

There are chapters on each of the SEEDS model’s elements and thoughts about how classroom experiences of hands-on democracy can demonstrate them. They form the main academic case for nurturing a democratic imagination, supported compellingly by reference to writers from Hannah Arendt to Amartya Sen and Talcott-Parsons.

Civics vs Hands on Democracy

Many advocate for more teaching of classroom civics to provide children with a better understanding of government, citizenship and democracy and of course this has its place. Bronwyn writes about developing the democratic imagination. How much more empowering real world decision making is in a child’s own environment than learning about the separation of judicial and executive powers or the role of Select Committees. Experiences mediated through the SEEDS model of enriched democracy in both the young and the adult world speak to Einstein’s maxim that “We cannot fix our problem with the same quality of thinking as we created it.” Expanding the public’s (as well as children’s) appetite for a richer and deeper kind of democratic engagement, giving communities the ability to envision new futures and electing a government that would respond to crises with “more democracy” point to the means by which environmental problems can be addressed in the future. Our generation is likely to leave our children’s generation with a worse environment than we inherited. Leaving young people bereft of a sense that democracy can help provide new thinking for creating robust, fair and lasting solutions would be to add insult to injury.

Jan Rivers, Convenor public good

Links

Publisher information

Short video introduction to the book by the author

Bronwyn’s blog

Latest Comments